IN TIME TO THE MUSIC: FROM DOOWOP TO FOLK ROCK

(A 60s CAMPUS AND NATION IN TRANSITION)

By Stephen E. Appell ’65

As the University’s Centennial Class entered in September 1961, the campus was rather placid, with most students interested in careers and traditional attachments to alma mater. The typical male student sported a crew-cut, a crewneck sweater, a button-down shirt, a pair of slacks, and loafers. The Cornell female was likely to wear her hair medium-length with a “flip,” and to be attired in a sweater, plaid skirt, knee socks, and loafers.

Few students seemed interested in politics, and there were few, if any, activists. Yet by the time we left in June 1965, something new was happening: we witnessed, or participated in, the crystallizing of student political awareness, especially of the Vietnam War and the civil rights movement. In 1964, a majority of the student body voted aid for fellow students who would take part in a Tennessee voter-registration project during the summer; this may be deemed the turning point in the direction of the Cornell constituency.

We saw the beginning of college women – and men – with long hair, dungarees, sandals, and backpacks. For some students, the traditional escape of beer was beginning to be supplanted, or augmented, with more controversial substances.

We would not remain at Cornell to experience the transformation fully, but the “rah-rah” life was about to yield, if only temporarily, to soul-searching and sit-ins, to Father Berrigan and the Black rebellion. The good-natured chanting of football slogans such as “The Navy’s goat is queer” at the 1961 encounter with the midshipmen from Annapolis would now be replaced by protests against ROTC and shouts of “power to the people.” We started at Cornell in one world, and left with the campus very much entering another.

Our music too underwent transition. When we entered, our rock and pop music consisted largely of the following elements:

--“Rockabilly,” an admixture of white country music and black rhythm-and-blues. The term itself is a synthesis of “rock” and “hillbilly.” This type of rock and roll, performed by white artists with twangy guitars, is exemplified by the early songs of Elvis Presley, such as Hound Dog; and Carl Perkins’s Blue Suede Shoes.

--“Rockabilly,” an admixture of white country music and black rhythm-and-blues. The term itself is a synthesis of “rock” and “hillbilly.” This type of rock and roll, performed by white artists with twangy guitars, is exemplified by the early songs of Elvis Presley, such as Hound Dog; and Carl Perkins’s Blue Suede Shoes.

--Black rhythm-and-blues (“R & B”), which derived from earlier blues and gospel influences, which had been largely confined to a Black audience until the mid-50s, and which was often introduced to the “mainstream” by so-called “cover records” of blander white artists like Pat Boone. The great R & B artists of the 50s, who became generally popular, included Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Fats Domino, and Sam Cooke.

--The ever-present folk element. Despite the outstanding folk-song tradition of such artists as Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and the Weavers, the folk style which predominated on the pop charts by 1960 was the relatively uncontroversial type of the Kingston Trio and the Brothers Four.

--The group-harmony sound of the city street corners, an offshoot of R & B, which came to be called “doowop.” This was originally an a cappella form (i.e., with no instrumental accompaniment); and featured a lead singer accompanied by a group singing background harmony which often consisted of nonsense syllables like “doo-wop shoo-bop-bop” and “dom dooby dom.” A well-known example was In the Still of the Night. In the 70s, this form was revived, if somewhat satirically, by the group Sha-Na-Na.

--Numerous dance-craze songs, like The Twist, which incorporated various of the above elements.

--Finally, the simple but pleasing love ballads of the late 50s and early 60s, more akin to pre-rock pop music, sung especially by such glamorous idols as Connie Francis and Paul Anka.

By the time we left Cornell, much had happened to the prevalent sounds. Doowop largely disappeared by mid-1962, with its vocal-group harmonies to resurface in a more grandiose fashion with the Four Seasons, Beach Boys, and the “wall-of-sound” productions of Phil Spector and the so-called “girl groups.” The folk-oriented pop sound became more politicized and issue-oriented, as witness Bob Dylan and Peter, Paul and Mary. The Black R & B influence manifested itself with greater pride, vigor, and commercial success with the rise of the “soul” sound, especially from Motown (Detroit); this development was surely related to the simultaneous expansion of Black consciousness and social freedom.

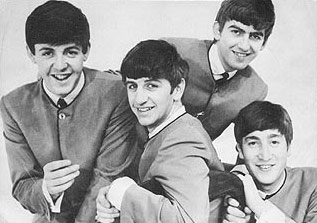

Our last two years at Cornell saw us inundated by the legendary “British invasion” headed by the Beatles, Rolling Stones, and Dave Clark Five. The works of British artists often were merely better, or poorer, imitations of those of American performers. But they contributed not only with more daring lyrics about social relationships, but also with more varied chord patterns and instrumentation which extended well beyond the simple patterns and accomplishments of preexistent rock-and-roll music.

While we were at Cornell in these years of change, struggling to make it and yet enjoying possibly our best years, the music was part of us. One recalls the constant playing of the jukebox in the Ivy Room (that designation now applies to an adjacent dining room), in Willard Straight Hall; the local bands such as Bobby Comstock and the Counts, and Bernie and the Cavaliers, at fraternity parties; the appearances of established stars for concerts and special weekends; or just the non-stop accompaniment of our radios while we typed up notes, completed a term paper, or studied for prelims and finals. Our music reflected our social outlook – whether in regard to relations with the opposite sex, or with society in general. For many, the songs reflect rich memories and are memories in themselves. Now, the songs and their times:

Fall 1961 (Term 1): How appropriate it was that in September, while I was traveling to Cornell from New York City for the first time, the radio played The Mountain’s High by Dick and DeeDee as we rambled through the Catskills, mirroring the mixture of regret and hope upon leaving the high school experience and friendships. Upon settling down in University Hall #5, I experienced the thrill of tuning in WMGM from New York (1050 on the AM radio dial; later country-station WHN and now gone altogether as a music station), and hearing a doowop song called Anniversary of Love by the Caslons (a typical group name in those days). Symbolically, I could hardly hear it through the static, as it kept fading in and out: the old music and old life were changing.

Now I would receive my music through WTKO, “Swinging Radio” (1470 on the AM dial), which amply supplied us with the current hits. (Who can forget the presumptuous dateline on WTKO news programs: “Washington… Moscow… Ithaca…” Never mind, Ithaca did assume a special place in our minds.) There would also be Cornell’s own WVBR, and the stations of other upstate towns, especially WKBW in Buffalo.

We experienced the beauties of our first Cornell autumn, and were awed by the chimes resounding from the Libe Tower as we dragged to 8 a.m. classes (on occasion). We marveled at the promise of sophomore quarterback Gary Wood and placekicker Pete Gogolak, while the supporting backfield of Tino, Telesh and Kavensky were all neutralized by injury.

In those exciting days, these songs stood out: Bobby Vee’s Take Good Care  of My Baby, written by the prolific Carole King and Gerry Goffin; Bristol Stomp by the Dovells, reflecting the ever-present dance theme in rock music; the Drifters’ catchy Sweets for My Sweet; the Lettermen’s smooth The Way You Look Tonight; and Ray Charles’s R & B classic, Hit the Road Jack. On the country side, Jimmy Dean narrated the tale of Big Bad John; and Brenda Lee sang about Fool No. 1. The Fleetwoods, progenitors of “soft rock,” bemoaned losing “her” to The Great Impostor. The first song I remember being constantly played on the Ivy Room jukebox was the lively Runaround Sue by Dion, which topped the national charts on October 23.

of My Baby, written by the prolific Carole King and Gerry Goffin; Bristol Stomp by the Dovells, reflecting the ever-present dance theme in rock music; the Drifters’ catchy Sweets for My Sweet; the Lettermen’s smooth The Way You Look Tonight; and Ray Charles’s R & B classic, Hit the Road Jack. On the country side, Jimmy Dean narrated the tale of Big Bad John; and Brenda Lee sang about Fool No. 1. The Fleetwoods, progenitors of “soft rock,” bemoaned losing “her” to The Great Impostor. The first song I remember being constantly played on the Ivy Room jukebox was the lively Runaround Sue by Dion, which topped the national charts on October 23.

As the days got shorter and our first winter vacation approached, the cold weather was offset by the warmth of Moon River (instrumentally by Henry  Mancini and vocally by Jerry Butler); the melancholy ballad Town Without Pity by Gene Pitney; a more traditional love ballad, ’Til, by the Angels; the Shirelles’ Baby It’s You, co-written by Burt Bacharach; and Elvis Presley’s beautiful ballad, Can’t Help Falling in Love. The big dance craze was the “twist,” epitomized by Chubby Checker’s definitive recording which hit No. 1 on the charts for a second time (originally appearing in 1960), Dear Lady Twist by Gary (U.S.) Bonds; and The Peppermint Twist of Joey Dee and the Starliters.

Mancini and vocally by Jerry Butler); the melancholy ballad Town Without Pity by Gene Pitney; a more traditional love ballad, ’Til, by the Angels; the Shirelles’ Baby It’s You, co-written by Burt Bacharach; and Elvis Presley’s beautiful ballad, Can’t Help Falling in Love. The big dance craze was the “twist,” epitomized by Chubby Checker’s definitive recording which hit No. 1 on the charts for a second time (originally appearing in 1960), Dear Lady Twist by Gary (U.S.) Bonds; and The Peppermint Twist of Joey Dee and the Starliters.

The Marvelettes gave us the first Motown hit to reach No. 1 with Please Mr. Postman. The Straight jukebox reflected our appreciation for the folk sound with the Highwaymen’s two-sided hit, Cotton Fields and The Gypsy Rover. The folk trend also resulted in a hit for the Tokens, who applied their doo-wop harmonies to The Lion Sleeps Tonight; it reached No. 1 on December 18 and stayed there over New Year’s Day.

Spring 1962 (Term 2): As we experienced and then recovered from the shock of our first finals, and acclaimed John Glenn as the first American to orbit the Earth, we learned from Gene Chandler that nothing can stop the Duke of Earl. Bruce Channel, in Hey! Baby, demanded: “I wanna know if you’ll be my girl.” The Lettermen begged, Come Back Silly Girl. Dion bragged how they called him The Wanderer; Don and Juan inquired, What’s Your Name? (“Is it Mary or Sue?”); the Sensations implored, Let Me In; and Connie Francis admonished, Don’t Break the Heart That Loves You, in her last No. 1 hit. Dee Dee Sharp perpetuated the dance theme with Mashed Potatoes Time, and backed up Chubby Checker in Slow Twistin’.

As the weather got warmer and invited hikes to downtown Ithaca for a meal, we heard Roy Orbison’s rockabilly classic, Dream Baby (How Long Must I Dream); Rick Nelson’s Young World; Soldier Boy by the Shirelles; the Crystals’ Uptown, one of the earliest pop-chart references to the “ghetto” existence; Gary U.S.” Bonds’s rousing Twist Twist Senora; and Johnny Angel, which TV star Shelley Fabares took to No. 1 on April 7. On the smoother side were Ketty Lester’s sultry Love Letters; Acker Bilk’s soothing clarinet in Stranger on the Shore; Ray Charles’s journey into “country” with I Can’t Stop Loving You; and the Ivy jukebox favorite, Scotch and Soda, by the Kingston Trio.

And all through the year, you’d be bound to hear Ray Charles’s 1959 R & B standard, What’d I Say, at any campus party.

Fall 1962 (Term 3): We returned to campus for a second year and Gary Wood’s superb season, fresh from a summer marked by Neil Sedaka’s lively Breaking Up Is Hard to Do; the Isley Brothers’ Twist and Shout, a campus favorite; Bobby Vinton’s sentimental Roses Are Red; Little Eva’s dance hit, The Loco-Motion; You Belong to Me, in which the Duprees successfully applied a doowop-style background to a pre-rock pop ballad; and the Four Seasons’ first hit, Sherry, replete with Frankie Valli’s inimitable falsetto.

We lived through a momentous October in which President Kennedy guided us through the Cuban missile crisis, and we saw the stirrings of strong political feelings on campus with ensuing demonstrations. Most popular songs did not reflect this turmoil, as we heard Johnny Mathis’s tender ballad Gina; Elvis Presley’s Return to Sender; Jimmy Clanton’s Venus in Blue Jeans; and the raucous Do You Love Me? (“now that I can dance”) by the Contours. Praise for social nonconformism did surface with He’s a Rebel, the label of which said it was sung by the Crystals but in which the lead was actually sung by Darlene Love, who made it to Broadway in the 1980s in the rock-review Leader of the Pack.

As 1962 drew to a close and we laughed at Vaughn Meader’s recorded  impersonations of the popular young President, a couple of instrumentals lit up the holiday period: Telstar by the Tornadoes, acknowledging our space achievements; and Wild Weekend by the Rebels, which was popular on the Straight jukebox. The Four Seasons repeated their success with Big Girls Don’t Cry; the Earls hit a nostalgic chord with the doowop Remember Then; Steve Lawrence clicked with Go Away Little Girl, and Bobby Vee with The Night Has a Thousand Eyes; and the Rooftop Singers capitalized on the persistent popularity of the folk sound with Walk Right In, which reached No. 1 on January 26.

impersonations of the popular young President, a couple of instrumentals lit up the holiday period: Telstar by the Tornadoes, acknowledging our space achievements; and Wild Weekend by the Rebels, which was popular on the Straight jukebox. The Four Seasons repeated their success with Big Girls Don’t Cry; the Earls hit a nostalgic chord with the doowop Remember Then; Steve Lawrence clicked with Go Away Little Girl, and Bobby Vee with The Night Has a Thousand Eyes; and the Rooftop Singers capitalized on the persistent popularity of the folk sound with Walk Right In, which reached No. 1 on January 26.

Spring 1963 (Term 4): As 1963 began, the Four Seasons may well have hit their peak with Walk Like a Man, which combined a march-like beat with a hymn-like melody in the refrain, to reach No. 1 on March 2. The Miracles demonstrated the growing power of Motown with You’ve Really Got a Hold on Me. A new dance sound arrived as Eydie Gorme told us to Blame It on the Bossa Nova. Dion sang of yet another female favorite, Ruby Baby. A smooth hit was Our Day Will Come by Ruby and the Romantics; a less sophisticated smash was I Will Follow Him by Little Peggy March. Peter, Paul and Mary continued to demonstrate preeminence in the folk area, with Puff the Magic Dragon. Mongo Santamaria had an instrumental Latin-beat hit with Watermelon Man.

At this time, Ithaca’s own Bobby Comstock and the Counts had their one major hit with Let’s Stomp (backed with I Want to Do It, a big favorite at Cornell parties when sung with more daring lyrics). The Orlons advised that all the hippies meet on South Street; the Rocky Fellers warned us to look out for Killer Joe; and the incomparable soul-man Jackie Wilson belted out Baby Workout. Chubby Checker abandoned his usual dance themes to make it with the lively Twenty Miles (“Twenty miles is a long, long way – but I GOT to see my baby every day!”)

A most significant development in rock music in early 1963 was the advent of Phil Spector’s “wall of sound,” with old-style group harmonies put to new beats and more sophisticated backgrounds. Spector’s wall of sound was achieved by the use of echo-chamber techniques and elaborate orchestral and choral accompaniments. Spector’s hits were usually sung by the so-called “girl groups;” today we would better just call them “female groups” given our raised consciousness.

Darlene Love, one of Spector’s top singers, finally had a hit in her own name with (Today I Met) The Boy I’m Gonna Marry. The upbeat Da Doo Ron Ron, by the Crystals and produced by Spector, exemplified the “girl-group” trend and became a hit late in the spring. A “girl-group” sound even more successful was He’s So Fine by the Chiffons; it hit No. 1 on March 30 and stayed there for four weeks, and provided musical inspiration for the strangely similar tones of My Sweet Lord by George Harrison, seven years later.

As we finished a second beautiful spring at Cornell, Lesley Gore first hit the charts with It’s My Party; Kyu Sakomoto showed that American hits could be sung in Japanese, with Sukiyaki; the Classics gave doowop one more shining moment on the charts with Till Then; the Essex came out with a soon-to-be No. 1 hit, Easier Said Than Done; and the Tymes released their beautiful harmonious ballad, So Much in Love, which was to reach No. 1 by August.

Fall 1963 (Term 5): We came back for a third year (and a final season of heroics by Wood and Gogolak), with the nation on a higher moral plane. The nuclear test-ban treaty had been signed in July. At the mass demonstration culminating the March on Washington on August 28, Dr. Martin Luther King had evoked the loftiest ideals with the immortal expression of his dream. Blowin’ in the Wind, written by Dylan and recorded by Peter, Paul and Mary, was sung at the demonstration and was appropriately a hit at the time. Many Cornellians cherished the pure folk songs of Odetta, Joan Baez, and Pete Seeger, with their lyrics reflective of the growing passion for social change. Trini Lopez, however, showed that the folk sound could perhaps be made more rock and less folk with If I Had a Hammer, a 1962 hit for P, P and M.

Not all was preoccupation with high ideals. During the summer, Jan and Dean had sung about another American obsession, the beach, in Surf City. The fellow prophets of California surf culture, the Beach Boys, led us into the fall with Little Deuce Coupe and the harmonious ballad, Surfer Girl. Continuing the high note of the female groups, the Angels scored with My Boyfriend’s Back, the Ronettes with Be My Baby, and the Crystals with Then He Kissed Me. The folk tradition had winners with the instrumental Washington Square by the Village Stompers, and Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right by Peter, Paul and Mary.

What was such a happy period for many of us was marred on November 22 (this writer’s 19th birthday) by the assassination of President Kennedy, whose vigor and growing idealism we would never forget. (We can all remember where we were when the news broke: I was in the Teagle Hall locker-room, having just played basketball.)

Still, life went on, as did the joyful sound of music. The Beach Boys instructed us to Be True to Your School; the Murmaids sang of Popsicles and Icicles; and the Kingsmen scored at the end of 1963 with the simple yet catchy Louie Louie, which became a dance favorite on campus. Lesley Gore had a top ballad with You Don’t Own Me (her producer was the now-renowned Quincy Jones), and Dionne Warwick had another with Anyone Who Had a Heart.

But with the turn of the year, the music scene belonged to John, Paul, George and Ringo, and rock music would never again be the same. On our winter holiday break, we heard I Want to Hold Your Hand, and it was No. 1 for seven weeks, beginning in February. The “British invasion” had begun. The Beatles proceeded to dominate the charts throughout the 60s, and they changed the sound of popular music for ever after.

Spring 1964 (Term 6): The spring of 1964 was a time of promise. The cold Ithaca February passed, and the spring warmth inspired walks down into the gorges to “catch the rays.” President Johnson had just announced a war on poverty and committed himself to meaningful civil rights legislation. American stars brought us some prominent hits, like the Four Seasons’ Dawn (Go Away) and Louis Armstrong’s show hit, Hello Dolly. The Beach Boys told us she’d have Fun, Fun, Fun till her daddy took the T-bird away. But this was the season of the Beatles.

Previously, stars spaced their hits at appropriate intervals to avoid overexposure. But the Beatles let loose with one release on top of another. This was the era of their simpler, happier songs: She Loves You (“yeah, yeah, yeah”), Please Please Me, Do You Want to Know a Secret, All My Loving, Can’t Buy Me Love. Perhaps it was their hair (not long by standards soon to be established), their novelty or charisma, their greater use of electric instruments, or their introduction of new chords into rock music. Whatever it was, America fell in love with them, and Cornellians were no exception.

The Beatles prompted instant imitation. The Dave Clark Five followed from England, with Glad All Over and then Bits and Pieces, but they were not as versatile. Others, like Peter and Gordon with World Without Love, invaded by performing songs written by the Beatles’ John Lennon and Paul McCartney. Americans Bobby Rydell and Bobby Vee attempted to emulate the Beatles’ styles and chord patterns. Terry Stafford, however, bucked the trend and sounded more like Elvis with Suspicion.

The spring ended with the Beach Boys’ double hit, I Get Around and Don’t Worry Baby; Mary Wells’s big Motown hit, My Guy, written by Smokey Robinson of the Miracles; the Beatles’ Love Me Do and P.S. I Love You; the Four Seasons scoring with Rag Doll; and the Dixie Cups marching off to The Chapel of Love. The 1964-65 World’s Fair was on in New York; the Mets had their new home in Shea Stadium; boxing champ Cassius Clay became Muhammad Ali; and President Johnson was rousing Congress to action. All was well, we thought, as our junior year came to a close.

Fall 1964 (Term 7): Over the summer, the Beatles had kept it going, particularly with a number of hits from their first movie, A Hard Day’s Night. The Supremes, featuring future superstar Diana Ross, hit No. 1 in late August with Where Did Our Love Go, and thereby perhaps sealed the success of the Motown label. As we returned, Roy Orbison was climbing the charts with Oh Pretty Woman; the Dave Clark Five slowed down their tempo with Because; and Chad and Jeremy bade farewell to the warm season with A Summer Song. Gale Garnett had a country-style song appropriate for us Cornell seniors: We’ll Sing in the Sunshine, which talked about spending one year – about all we had left in our undergraduate period at Cornell – with a loved one.

Fall 1964 (Term 7): Over the summer, the Beatles had kept it going, particularly with a number of hits from their first movie, A Hard Day’s Night. The Supremes, featuring future superstar Diana Ross, hit No. 1 in late August with Where Did Our Love Go, and thereby perhaps sealed the success of the Motown label. As we returned, Roy Orbison was climbing the charts with Oh Pretty Woman; the Dave Clark Five slowed down their tempo with Because; and Chad and Jeremy bade farewell to the warm season with A Summer Song. Gale Garnett had a country-style song appropriate for us Cornell seniors: We’ll Sing in the Sunshine, which talked about spending one year – about all we had left in our undergraduate period at Cornell – with a loved one.

The passage of the Gulf of Tonkin resolution by Congress had been a portent of things to come, but we kept looking at the bright side, with President Johnson overwhelmingly elected to a full term, Dr. King receiving the Nobel Peace Prize, and ardent Big Red fans rationalizing why their football team finished 3-5-1 on the gridiron. (The Big Red did score an Ivy League record of 57 points against Columbia.)

As the fall turned cooler, Motown kept rising: We were Dancing in the Street with Martha and the Vandellas, and the Supremes followed up with Baby Love. The Kinks, with You Really Got Me, unwittingly provided a local band, playing at a November Fall Weekend party near my apartment, with the song by which to keep me awake, while I struggled to rest for the Law Schools Admission Test the following day.

The holiday season was marked by the Beatles’ I Feel Fine and She’s a Woman, and the Zombies’ She’s Not There. Speaking of women, the Ronettes gave us Walking in the Rain; the Shangri-Las, forerunners of later hard-woman singers, eulogized the Leader of the Pack; and the Supremes attained No. 1 for a third time with Come See About Me. From England, the raunchy Rolling Stones scored with Time Is on My Side, and the mellow Petula Clark debuted on the American charts with Downtown. The Righteous Brothers, whose powerful voices suggested the influence of Black gospel and whose sound was appropriately dubbed “blue-eyed soul,” had a major hit with You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling, produced by Spector. We had one term to go before we left Ithaca to face the world.

Spring 1965 (Term 8): This last term was filled with contradictions. We were determined to party as much as ever; and we thrilled to Cornell’s basketball team, led by Dave Bliss, Steve Cram, and Bob DeLuca, as they upset Bill Bradley and Princeton, 70-69, on January 16, and led the Ivy race well into February, only to finish 19-5 overall, and second in the Ivy League.

The brutality against rights marchers at Selma appalled us, but President Johnson pushed for a Voting Rights Act, proclaiming before Congress, in the words of the civil rights hymn, that “We shall overcome.” Yet the Vietnam War was expanding, and the Marines were sent to the Dominican Republic. Cornellians became more politicized, with teach-ins to discuss the war, and protests at the campus appearances of Ambassador Averell Harriman and at the ROTC Presidential Review. We were just viewing the tip of the iceberg as to what was to come at Cornell in the second half of the decade.

But the beat went on. Dance themes were about exhausted, but Cannibal and the Headhunters synthesized them all in Land of 1,000 Dances. The Temptations had their first No. 1 hit out of Motown with My Girl. The Four Seasons, with Bye Bye Baby (Baby Goodbye) had one of the first rock hits dealing with an extramarital love affair. The dynamic Shirley Bassey had the bit hit, Goldfinger, from the James Bond movie. The Supremes hit No. 1 on March 27 with Stop! In the Name of Love.

The British kept coming with Ferry Across the Mersey (Gerry and the Pacemakers); Eight Days a Week and Ticket to Ride (Beatles); and Can’t You Hear My Heart Beat and Mrs. Brown, You’ve Got a Lovely Daughter (Herman’s Hermits). The “soul” of Motown kept rolling along with such songs as I’ll Be Doggone by emerging superstar Marvin Gaye; Shotgun by Junior Walker and the All-Stars; Nowhere to Run by Martha and the Vandellas; I Can’t Help Myself by the Four Tops; and the Supremes’ fifth consecutive No. 1 hit, Back in My Arms Again.

Time was running out. The plaid skirts and the knee socks were about gone, and the long hair, dungarees, and sandals were arriving. The Beach Boys kept the carefree California sound alive with Help Me Rhonda, but more indicative of the trend was Bob Dylan’s folk-rock Mr. Tambourine Man, which as recorded by the Byrds was popular by May and reached No. 1 shortly after graduation. Barry McGuire’s Eve of Destruction, a folk-rock commentary on turmoil and injustice in the world, was only two months away. The Spector sound and the groups associated with it had about run their course.

Now it was time for the Animals, Yardbirds, Stones, and Byrds, and soon thereafter for Simon and Garfunkel, Donovan, the Lovin’ Spoonful, the Association, the Monkees, and the Mamas and Papas. Dylan would have folk-rock hits which would rile his purist folk followers. The soul sound would attain greater heights, with the performers already noted and also Aretha Franklin, Otis Redding, James Brown, Stevie Wonder, and Wilson Pickett. The Beatles would continue to dominate the 60s, expanding their repertoire.

The ultimate bittersweet moment came on June 14, at the Commencement ceremonies of the Centennial Class. The Beau Brummels told us they would cry Just a Little at having to go; and Chad and Jeremy sang solemnly about “losing you” in Before and After. One could almost imagine that they timed these hits for our reluctant departure from Big Red Country.

A personal epilogue: Associations between Cornell and the music could never cease. In 1982, I made one of my many pilgrimages to Cornell since our 1965 farewell, but this was the first football weekend at which I was accompanied by my first son, Sanford, then only 5 ½ years old but already a lover of music and sports. We sat in the room of the Straight now designated as the Ivy Room, and our eyes lit up at the sight of the jukebox. Someone played Blue Eyes, a beautiful ballad by Elton John, an artist who had not yet been heard during our college years. It was as if I was groping for a new association between Cornell and the music. We hastened to the record store in Collegetown, and we bought Blue Eyes to take home with us.

Over the years, playing music on the radio, CDs, and iPod have figured prominently in my enjoyment of visits to Cornell.

Time has elapsed, but the feelings have not been erased. The memories of the Cornell years remain, and the music is there to reinforce them.

(Note: This article is a slightly-revised version of the article that appeared in Cornell Alumni News magazine, July 1985.)